Scaling Mastodon

What it takes to house 43,000 users

Eugen Rochko

Strategy & Product Advisor, Founder

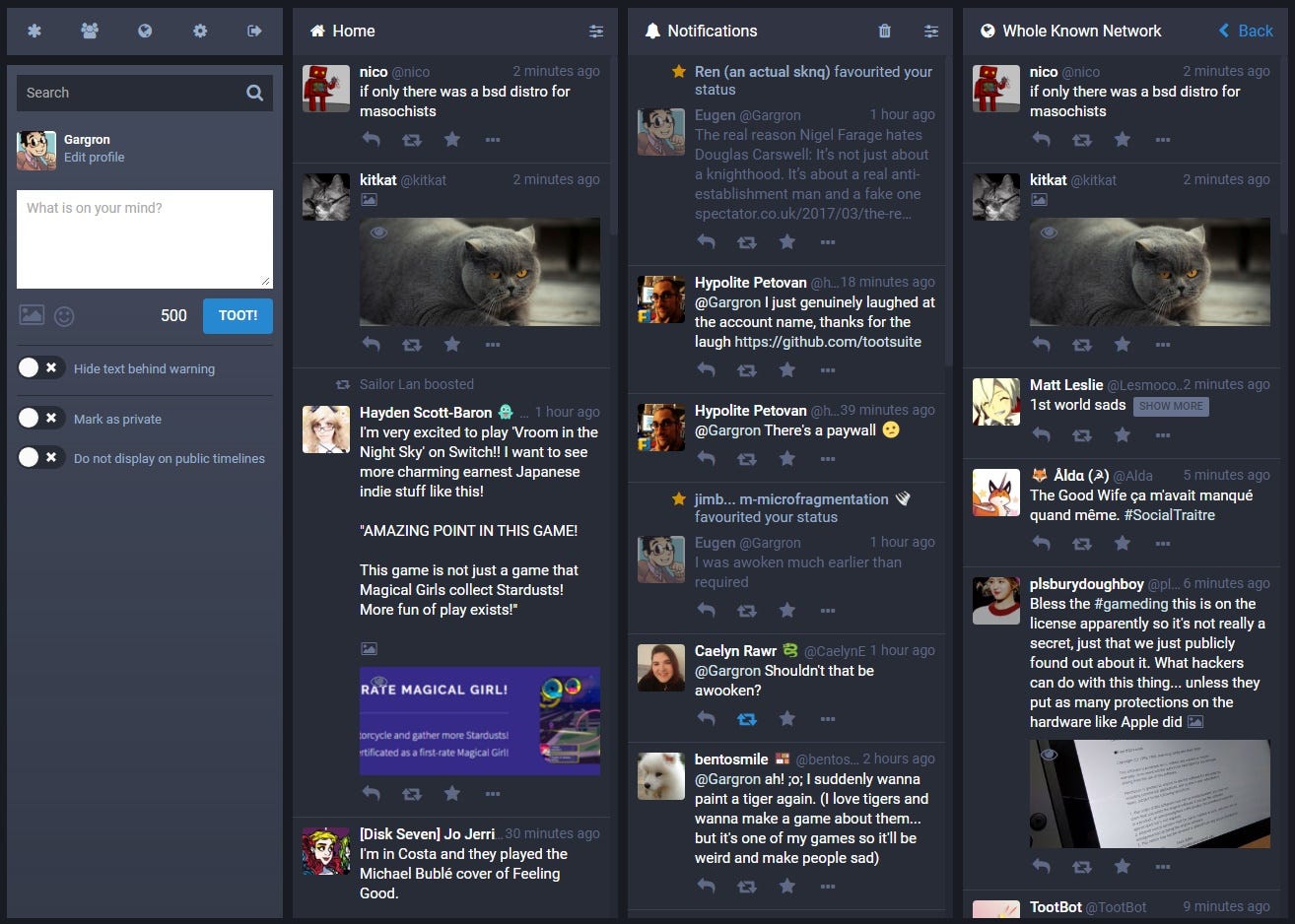

My instance mastodon.social has recently surpassed 43,000 users. I have closed registrations both to have more time to investigate the infrastructure and ensure a good experience for existing users, and to encourage more decentralization in the network (with a wonderful effect — the Mastodon fediverse now hosts over 161,000 people spread out over more than 500 independent instances!)

But providing a smooth and swift service to 43,000 users takes some doing, and as some of the other instances are approaching large sizes themselves, it is a good time to share the tips & tricks I learned from doing it.

Mastodon consists of two parts that scale differently: databases, and code. Databases scale vertically. That means, it’s a lot easier and more cost efficient to buy a super beefy machine for your database, than it is to spread the database over multiple machines with sharding or replication. The Mastodon code on the other hand, scales horizontally — run it from as many machines as you want, concurrently, and load balance the web requests, and you’re good.

First of all, where does the load on Mastodon come from?

The act of browsing and using the site requires the user’s HTTP requests to be answered. Every Puma worker (WEB_CONCURRENCY) can answer MAX_THREADS of requests at the same time. If every worker’s every thread is busy answering something, the new request must wait. If it has to wait too long, it is canceled with a timeout. That means, you need more workers and threads to be able to handle a higher request throughput.

Being connected to the streaming API means a constantly open connection through nginx to the streaming API service. The streaming API itself, I do not notice being strained from a high number of connections, but nginx requires a high limit on open files (worker_rlimit_nofile) and a high number of worker_connections to keep the connections up. Thankfully, nginx is quite lightweight even with such high parameters.

Actual activity on the site, like sending messages, following or unfollowing people, and many more things that people can do, all generates background jobs that must be processed by Sidekiq. If they are not processed in time, they start queuing up in a backlog, and it becomes noticeable when a toot you wrote reaches your followers only 1 hour later. That means, more Sidekiq workers are needed to be able to process more activity.

Those are the basic principles of Mastodon scaling. However, there is more.

Each time you scale horizontally, you are putting more strain on the database, because web workers and background workers and the streaming API all need database connections. Each service uses connection pools to provide for their threads. This can go up to 200 connections overall easily, which is the recommended max_connections on a PostgreSQL database with 16GB of RAM. When you reach that point, it means you need pgBouncer. pgBouncer is a transparent proxy for PostgreSQL that provides pooling based on database transactions, rather than sessions. That has the benefit that a real database connection is not needlessly occupied while a thread is doing nothing with it. Mastodon supports pgBouncer, you simply need to connect to it instead of PostgreSQL, and set the environment variable PREPARED_STATEMENTS=false

Simply spinning up more Sidekiq processes with the default recommended settings may not be the silver bullet for processing user activity in time. Not all background jobs are created equal! There are different queues, with different priorities, which Sidekiq works with. In Mastodon, these queues are:

- default: responsible for distribution of toots into local follower’s timelines

- push: delivery of toots to other servers and processing of toots incoming from other servers, before they are queued up for distribution to local followers

- pull: download of conversations, user avatars and headers, profile information

- mailers: sending of e-mail through the SMTP server

I have ordered them in the order of importance. The default queue is the most important, because it directly and instantly affects user experience on your Mastodon instance. Push is also important, because it affects your followers and contacts from other places. Pull is less important, because downloading that information can wait without much harm. And finally, mailers — there is usually not that much e-mail being sent from Mastodon, anyway.

When you have a Sidekiq process with a defined order of queues like -q default -q push -q pull -q mailers, it first checks the first queue, if nothing is there, the next one, etc. That is, each thread defined by the -c (concurrency) parameter, does that. But I think you must see the problem — if you suddenly have 100 jobs in the default queue, and 100 in the push queue, and you only have 25 threads working on all of them, there will be a huge delay before Sidekiq will ever get to the push ones.

For this reason, I found it useful to split queues between different Sidekiq processes on different machines. A couple responsible only for the default queue, a couple only responsible for push, pull, etc. This way, you are not getting too much delay on any type of user-facing action.

Another big revelation, though obvious in hindsight, is that it is less effective to set a high concurrency setting on a single Sidekiq process, than it is to spin up a couple independent Sidekiq processes with lower concurrency settings. Actually, the same is true for Puma workers — more workers with less threads work faster than less workers with more threads. This is because MRI Ruby does not have native threads, so they cannot be run truly in parallel, no matter how many CPUs you have. The only drawback is this: While threads share the same memory, separate processes don’t. That means, more separate processes consumes more RAM. But if you have free RAM on your server doing nothing, it means you should split up a worker into more workers with less threads.

The current mastodon.social infrastructure looks like this:

2x baremetal C2M (8 cores,16GB RAM) servers:

- 1 running PostgreSQL (with pgBouncer on top) and Redis

- 1 running 4x Sidekiq processes between 10–25 threads each

6x baremetal C2S (4 cores, 8GB RAM) servers:

- 2 running Puma (8x workers, 2x threads each), Sidekiq (10 threads), streaming API

- 1 running Nginx load balancer, Puma (8x workers, 2x threads each, Sidekiq (2 threads), streaming API

- 2 running Sidekiq (20 threads)

- 1 running Minio for file storage with a 150GB volume

Most of these are new additions since the surge of Internet attention — before that mastodon.social was serving 20,000 users (most of whom were, to be fair, not active the same time) with just the DB server, 2 app servers and 1 Minio server. At the same time, the v1.1.1 release of Mastodon includes a variety of optimizations that at least doubled the throughput of requests and background jobs compared to the first day of going viral.

At the time of writing, mastodon.social is servicing about 6,000 open connections, with about 3,000 RPM and an average response time of 200ms.