Why does decentralization matter?

Eugen Rochko

Strategy & Product Advisor, Founder

Japanese translation is available: なぜ脱中央集権(decentralization)が重要なのか?

I’ve been writing about Mastodon for two whole years now, and it occurred to me that at no point did I lay out why anyone should care about decentralization in clear and concise text. I have, of course, explained it in interviews, and you will find some of the arguments here and there in promotional material, but this article should answer that question once and for all.

decentralization, noun: The dispersion or distribution of functions and powers; The delegation of power from a central authority to regional and local authorities.

fediverse, noun: The decentralized social network formed by Mastodon, Pleroma, Misskey and others using the ActivityPub standard.

So why is it a big deal? Decentralization upends the social network business model by dramatically reducing operating costs. It absolves a single entity of having to shoulder all operating costs alone. No single server needs to grow beyond its comfort zone and financial capacity. As the entry cost is near zero, an operator of a Mastodon server does not need to seek venture capital, which would pressure them to use large-scale monetization schemes. There is a reason why Facebook executives rejected the $1 per year business model of WhatsApp after its acquisition: It is sustainable and fair, but it does not provide the same unpredictable, potentially unbounded return of investment that makes stock prices go up. Like advertising does.

If you are Facebook, that’s good for you. But if you are a user of Facebook… The interests of the company and the user are at odds with each other, from which the old adage comes that if you are not paying, you are the product. And it shines through in dark patterns like defaulting to non-chronological feeds (because it’s hard to tell if you’ve seen everything on the page before, it leads to more scrolling or refreshing, which leads to more ad impressions), sending e-mails about unread notifications that don’t actually exist, tracking your browsing behaviour across the internet to find out who you are…

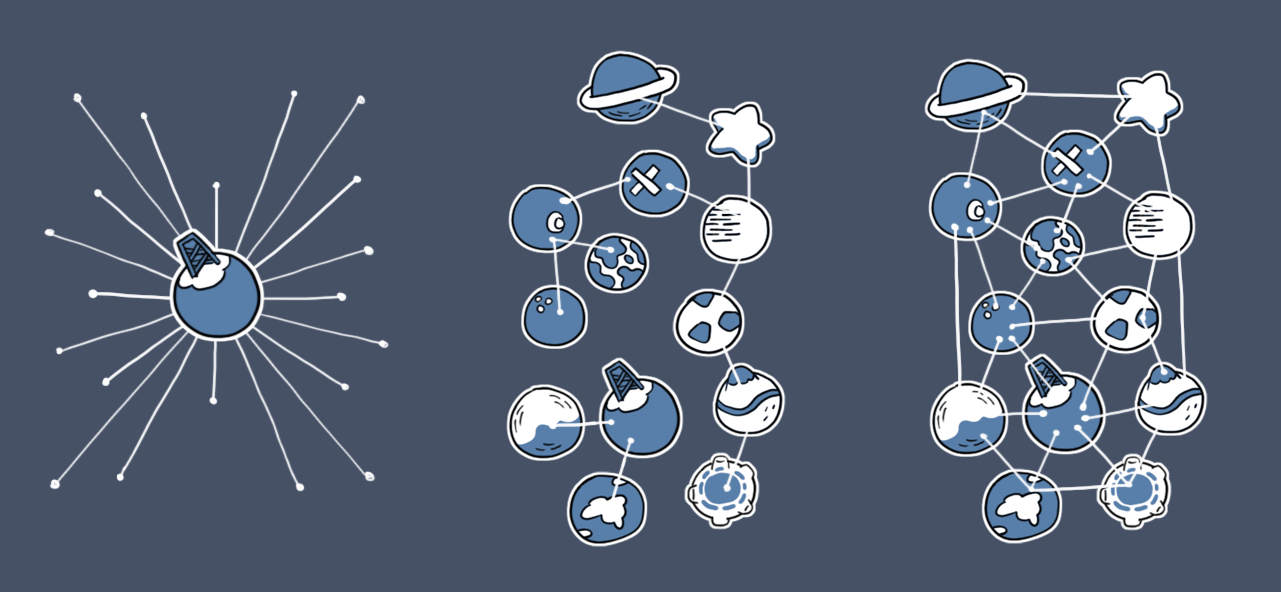

Decentralization is biodiversity of the digital world, the hallmark of a healthy ecosystem. A decentralized network like the fediverse allows different user interfaces, different software, different forms of government to co-exist and cooperate. And when some disaster strikes, some will be more adapted to it than others, and survive what a monoculture wouldn’t. You don’t have to think long for recent examples–consider the FOSTA/SESTA bill passed in the US, which turned out to be awful for sex workers, and which affected every mainstream social network because they are all based in the US. In Germany, sex work is legal, so why should sex workers in Germany be unable to take part in social media?

A decentralized network is also more resilient to censorship–and I do mean the real kind, not the “they won’t let me post swastikas” kind. Some will claim that a large corporation can resist government demands better. But in practice, commercial companies struggle to resist government demands from markets where they want to operate their business. See for example Google’s lackluster opposition to censorship in China and Twitter’s regular blocks of Turkish activists. The strength of a decentralized network here is in numbers–some servers will be blocked, some will comply, but not all. And creating new servers is easy.

Last but not least, decentralization is about fixing power asymmetry. A centralized social media platform has a hierarchical structure where rules and their enforcement, as well as the development and direction of the platform, are decided by the CEO, with the users having close to no ways to disagree. You can’t walk away when the platform holds all your friends, contacts and audience. A decentralized network deliberately relinquishes control of the platform owner, by essentially not having one. For example, as the developer of Mastodon, I have only an advisory influence: I can develop new features and publish new releases, but cannot force anyone to upgrade to them if they don’t want to; I have no control over any Mastodon server except my own, no more than I have control over any other website on the internet. That means the network is not subject to my whims; it can adapt to situations faster than I can, and it can serve use cases I couldn’t have predicted.

Any alternative social network that rejects decentralization will ultimately struggle with these issues. And if it won’t perish like those that tried and failed before it, it will simply become that which it was meant to replace.

Digging deeper: